Lee Robinson (an important guy at Cursor) wrote a banger post about migrating Cursor from a CMS back to raw code and markdown. He did it in three days, spent $260 in tokens, and deleted 322K lines of code.

Reading it, I found myself nodding along. A lot.

My WordPress site had become a slug. Not just for visitors (though yes, my PageSpeed Insights were embarrassing) but for me. Most of my blog posts are over 3,000 words long, and for some reason, the Gutenberg editor gets very sluggish at that point.

I’d been thinking of rolling my own CMS but what Lee is advocating for is something much simpler. Just Markdown files.

So I (Claude Code, I mean) rebuilt my entire blog from scratch with Astro + MDX (which lets you use JSX components in Markdown) and hosted it on Cloudflare Pages.

We (CC and I) did it in 3 hours and $0 in tokens (ok fine I’m on the Claude Code Max plan but still, that cost is divided over all my projects so it’s near 0). Here’s how it went.

The Problem with A CMS

I think we can all agree that CMSes are… bloated. My WordPress setup, for example, had accumulated layers:

- Yoast SEO (a plugin to manage meta tags… which are just HTML)

- WP Super Cache (a plugin to make WordPress fast… which shouldn’t be slow)

- Various security plugins (to protect against attacks… that target WordPress specifically)

- A theme I’d customized so heavily it was basically unmaintainable

- Overpriced Godaddy hosting. And Godaddy is trash.

I believe we are moving to a world where humans will primarily interact with AI agents that do work on their behalf. And to Lee’s point, if you’re using AI agents in your workflows, then every layer between your agent and the final work output is an additional layer of complexity your agent has to navigate.

When I wanted to update a post, I couldn’t just tell my agent “update the code in my latest tutorial”. I had to log into WordPress, navigate to the post, wait for the editor, update the code snippet manually, and save. The AI-powered workflow I used for everything else in my life didn’t apply to my own content.

Wait, Do We need a CMS?

Sanity, which is the CMS Cursor used, wrote a response to Lee’s post, and they weren’t entirely wrong. Their core arguments:

- What Lee built is still a proto-CMS – just distributed across git, GitHub permissions, and custom scripts

- Git isn’t a content collaboration tool – merge conflicts on prose are miserable

These are valid concerns for teams. For a media company with 200 writers, approval chains, and content appearing across web, mobile, and email? Yeah, you probably need a real CMS.

And maybe you can vibe code your own, but the edge cases might grow over time.

But some of their other arguments don’t hold up as well:

“Markdown files are denormalized data” – Sanity argues that if your pricing lives on three pages, you’re updating three files. But this is exactly what components solve. In Astro, you create a <Pricing /> component that pulls from a single source. Change it once, it updates everywhere it’s used.

“Agents can grep, but can’t query” – They say you can’t grep for “all posts mentioning feature X published after September.” But AI agents don’t just grep. They use semantic search. Claude Code can read frontmatter dates, understand content contextually, and reason about what you’re asking for.

In fact, most of Sanity’s arguments really only make sense for massive enterprise companies with complex content processes. And at that scale, the CMS isn’t the issue. It’s the process itself.

For everyone else, everyone on WordPress, Webflow, Framer, Wix, Weebly, what have you, the “you’ll end up building a CMS” argument assumes we need CMS features.

And my biggest revelation from this project is… maybe not? I personally need:

- A place to write text

- A newsletter signup form

- Images

- Tracking scripts (google analytics, etc)

- Custom CTAs and components

That’s it! Everything else is overhead.

So yeah, I agree with Sanity. Don’t build your own CMS. But the real question isn’t should you build your own CMS (you shouldn’t), but do you actually need a CMS in the first place?

ok no CMS, but Why Astro?

Most frameworks like Next.js or Gatsby ship JavaScript to the browser for everything, even if a page is just static text. That’s because they hydrate the entire page as a React app.

Astro does the opposite. By default, it renders your components to HTML at build time and ships zero JavaScript. A blog post with just text and images is just pure HTML and it loads instantly.

When you actually need interactivity, like a newsletter form, or an interactive demo, you add a client: directive to that specific component:

---

import NewsletterForm from '../components/NewsletterForm.jsx';

---

<article>

<p>This is just HTML, no JS shipped...</p>

<!-- Only this component gets JavaScript -->

<NewsletterForm client:visible />

</article>

This is called Islands Architecture. Your page is a sea of static HTML with small islands of interactivity where you need them.

For my blog, that means 95% of every page is static HTML. The only JavaScript is Kit’s embed script for newsletter signups. My pages went from 200KB+ on WordPress to under 50KB on Astro.

What About Images?

This was my first concern. WordPress handles image optimization automatically (with enough plugins). Would I be manually running everything through TinyPNG?

Nope. Astro has built-in image optimization. You drop images in src/assets/, reference them in your markdown, and Astro handles the rest at build time – WebP conversion, responsive srcset, lazy loading, proper aspect ratios, other technical terms I had to learn about when trying to optimize my WP.

What About SEO?

Yoast SEO is really just a GUI for meta tags. In Astro, your layout handles it:

---

const { title, description, image } = Astro.props;

---

<head>

<title>{title}</title>

<meta name="description" content={description} />

<meta property="og:title" content={title} />

<meta property="og:description" content={description} />

<meta property="og:image" content={image} />

<link rel="canonical" href={Astro.url} />

</head>

Your blog post frontmatter provides the values:

---

title: "Building AI Agents from Scratch"

description: "A step-by-step guide to building coding agents with Python..."

image: "./cover.png"

---

For sitemaps: npx astro add sitemap. It auto-generates on build.

What About Caching?

This was my favorite realization: you don’t need caching plugins when your site is already static.

WP Super Cache exists because WordPress dynamically generates pages on every request. That’s expensive, so you cache the output.

Astro pre-generates everything at build time. Your pages are already HTML files sitting on a CDN. There’s nothing to cache dynamically. Cloudflare serves them from edge locations worldwide with automatic caching headers.

My WordPress site with caching plugins was slower than my Astro site with no caching at all.

What About Security?

Another plugin category that becomes irrelevant. WordPress security plugins exist because WordPress has attack surfaces – a database, PHP execution, a login page, plugin vulnerabilities.

Static HTML files can’t be hacked the same way. There’s no database to SQL inject. No PHP to exploit. No admin panel to brute force. The attack surface basically doesn’t exist.

What About Analytics?

On WordPress, I had a plugin for this. On Astro, it’s one line in your base layout:

<script defer data-domain="siddharthbharath.com" src="you-analytics-script-goes-here"></script><br>That’s it. Every page inherits from the layout, so every page gets tracking. Swap in Google Analytics, Meta pixel, or whatever you use, it’s all the same.

What About Newsletter Forms?

My blog has Kit signup forms scattered throughout posts. Would I lose the ability to embed forms easily?

Turns out it’s simpler than WordPress. I created a reusable component:

---

const { formId, title } = Astro.props;

---

<div class="newsletter-form">

{title && <h3>{title}</h3>}

<script async src={`https://f.kit.com/${formId}/script.js`}></script>

</div>

Now in any MDX post, I just drop in:

Some content about AI agents...

<KitForm formId="abc123" title="Get the free cheat sheet" />

More content here...

Claude Code knows about this component. When I say “add a newsletter signup after the introduction,” it adds the <KitForm /> tag in the right place. No shortcode syntax to remember, no plugin conflicts.

What About Code Blocks?

Almost all of my blog content contains this. In WordPress I need a plugin. In Astro, syntax highlighting is built in via Shiki. You write fenced code blocks in markdown:

```python

def hello():

print("Hello, world!")

```

Astro renders them as beautifully styled HTML at build time.

You can configure the theme in astro.config.mjs:

export default defineConfig({

markdown: {

shikiConfig: {

theme: 'one-dark-pro',

wrap: true,

},

},

});What About Video Embeds?

YouTube and Vimeo embeds are just iframes. They work in markdown out of the box. But if you want something cleaner, you can create a component:

---

const { url, title } = Astro.props;

const videoId = url.match(/(?:youtube\.com\/watch\?v=|youtu\.be\/)([^&]+)/)?.[1];

---

<div class="video-embed">

<iframe

src={`https://www.youtube.com/embed/${videoId}`}

title={title}

loading="lazy"

allowfullscreen

/>

</div>

Then in your MDX:

<VideoEmbed url="https://youtube.com/watch?v=abc123" title="How to build AI agents" />

The loading="lazy" means videos don’t load until the user scrolls to them. Better performance than any WordPress embed plugin I’ve used.

What About Custom Pages?

Astro isn’t just for blogs. It’s a full static site generator. I have a homepage, about page, services page, and contact page, all custom designed.

Each page is just a file in src/pages/:

src/pages/

├── index.astro → Homepage with hero, featured posts, services

├── about.astro → Bio, experience, personal stuff

├── services.astro → Consulting offerings with CTAs

├── contact.astro → Contact form

└── blog/ → Blog listing and posts

You can share layouts across pages, create reusable components, and style everything with Tailwind or plain CSS. It’s as flexible as any custom WordPress theme, but without the PHP spaghetti.

How I Built It

Ok, hopefully I’ve sold you on why you should roll your own non-CMS. Let me walk through exactly what I did.

Step 1: Create the PRD

Before touching any code, I opened Claude (the regular chat, not Claude Code) and described what I wanted:

I want to rebuild my WordPress blog as a static site with Astro.

Here's what I need:

Pages:

- Homepage with hero, featured posts, services overview, newsletter signup

- About page with my background and experience

- Services page for my consulting offerings

- Contact page with a form

- Blog listing and individual post pages

Features:

- MDX for blog posts so I can embed components

- Tailwind for styling

- Kit newsletter forms

- Syntax-highlighted code blocks

- Image optimization

I want to deploy on Cloudflare Pages. Can you create a detailed PRD

I can give to Claude Code?

Claude generated a comprehensive PRD with the site structure, component specs, frontmatter schema, SEO requirements, and deployment steps. I refined it over a few back-and-forths until it covered everything.

Spend time on the PRD. The better your spec, the better Claude Code’s output. I probably spent 30 minutes getting the PRD right before writing any code.

Step 2: Scaffold the Project

With the PRD ready, I set up the project infrastructure. Open your terminal:

# Create the Astro project with the blog template

npm create astro@latest my-blog -- --template blog

cd my-blog

# Add the integrations we need

npx astro add tailwind

npx astro add mdx

npx astro add sitemap

# Initialize git

git init

git add .

git commit -m "Initial Astro scaffold"

# Create a GitHub repo and push

gh repo create my-blog --public --source=. --push

If you don’t have the GitHub CLI (gh), you can create the repo manually on GitHub and push with:

git remote add origin https://github.com/yourusername/my-blog.git

git push -u origin main

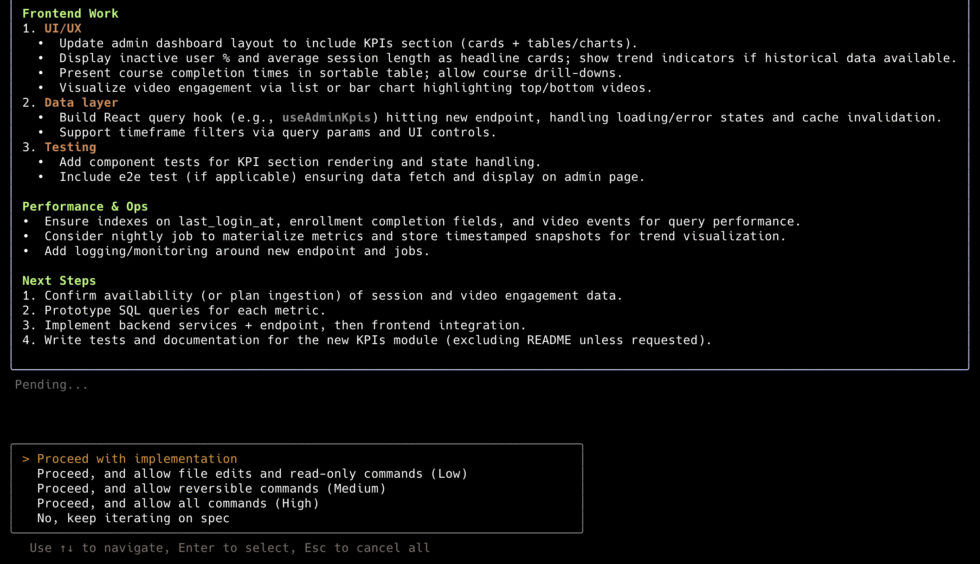

Step 3: Start Building with Claude Code

Now the fun part. Navigate to your project folder and start Claude Code:

cd my-blog

claude

I pasted in my PRD and told Claude Code to start building:

In this project, we're rebuilding my blog. Read the PRD and start working on it - PRD.md

Start with the base layout, navigation, and footer. Then build out

the homepage. Don't import all my content yet - just create 3 sample

blog posts so we can nail the design first.

The initial PRD included my core pages plus just three representative blog posts. This was intentional as I didn’t want to import dozens of posts before getting the design right. Better to iterate on the design with sample content, then bulk import once the templates are solid.

Claude Code scaffolded the layouts, created the component structure, and built out the homepage. The initial output was functional but generic. That “Tailwind AI slop” look you’ve seen a thousand times.

Step 4: Nail the Design

This is where things got interesting. I’ve been using a specific art style for my blog images, a retro-futuristic aesthetic inspired by 70s European sci-fi comics. I wanted the site design to complement that.

I gave Claude Code this prompt:

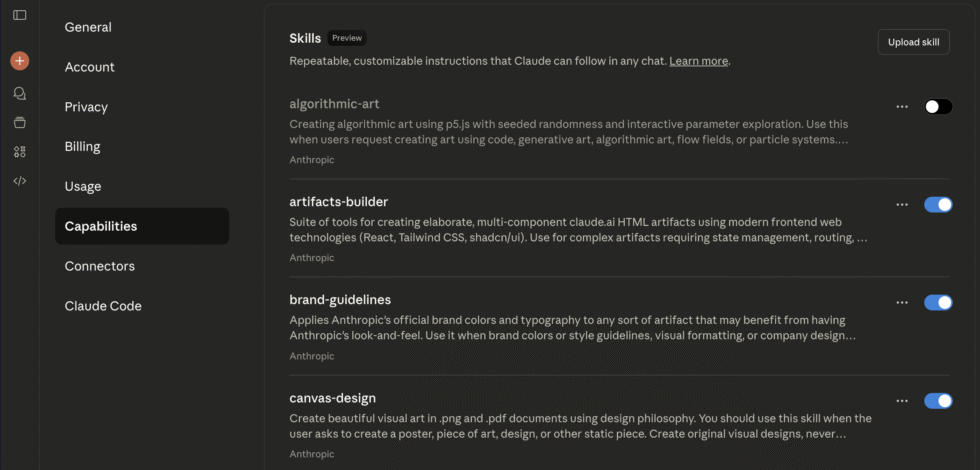

Use the frontend-design skill, then redesign the site to match this art style I use for my blog images:

"Retro-futuristic comic illustration in ligne claire style, Moebius-inspired. Clean linework, flat bold colors, highly detailed sci-fi architecture with intricate panels and cables. Cinematic perspective, surreal atmosphere, blending futuristic technology with timeless themes. Minimal shading, vibrant but muted tones, graphic novel aesthetic, 1970s European sci-fi magazine art."

Translate this aesthetic into web design: clean lines, bold but muted color palette, plenty of whitespace, subtle geometric accents. The typography should feel slightly retro but readable.Claude Code one-shotted it:

The frontend-design skill gave it the principles for high-quality UI work, and the specific art direction gave it a target aesthetic. It’s an impressive upgrade from my current (soon to be old) website, which I painstakingly created in WordPress:

Oh and it’s fully mobile optimized.

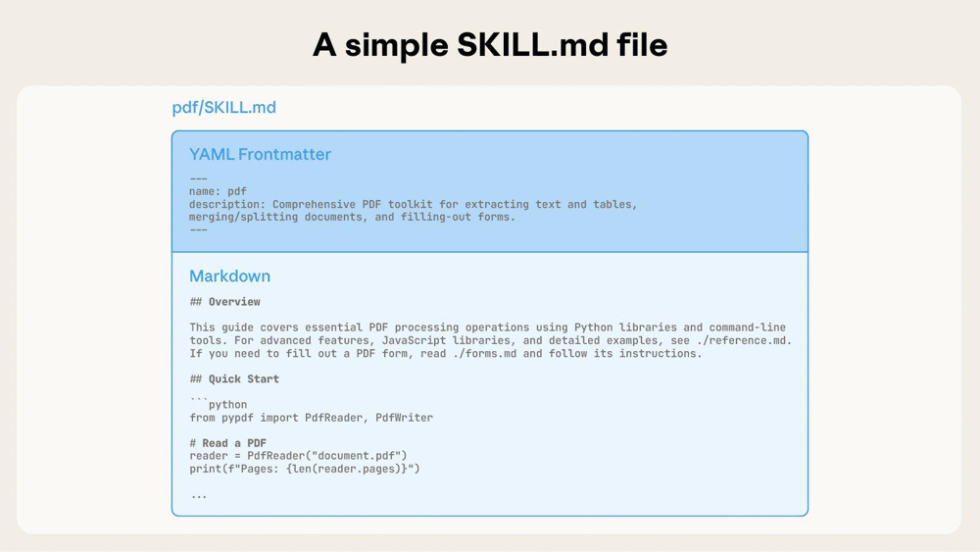

Use Skills. Read my Claude Skills post to learn more.

Migrating the Content

With all the core pages, and the design done, I just need to import the rest of my blog content and I can launch this.

This is where I am right now. The migration is still in progress as I publish this post, but here’s the process.

WordPress gives you an XML export (Tools → Export → All content). The file is… not pretty. I used wordpress-export-to-markdown to convert posts:

npx wordpress-export-to-markdown --input export.xml --output src/content/blog

Then I had Claude Code clean up the output:

Go through each markdown file in src/content/blog and:

1. Fix image paths to point to src/assets/images

2. Remove WordPress shortcodes

3. Convert any embedded forms to <KitForm /> components

4. Ensure frontmatter matches our schema

5. Rename to .mdx extension

It handles about 80% automatically. The remaining 20% is edge cases like weird formatting, broken embeds, posts that referenced WordPress-specific features.

The images are the tedious part. WordPress stores them in wp-content/uploads with date-based folders. I’m downloading them all, dropping them in src/assets/images/, and letting Claude Code update the paths in each post.

Pro tip: Don’t try to migrate everything at once. I’m doing it in batches of 10 posts at a time, verify they render correctly, commit, repeat. It’s slower but you catch issues early instead of debugging 50 broken posts at once.

I’ll update this post once the full migration is complete. For now, the old WordPress site is still live (you’re reading it!) at the original domain while I work through the backlog.

Deploying to Cloudflare Pages

I looked at three options: Netlify, Vercel, and Cloudflare Pages. All three work great with Astro and have generous free tiers. Here’s why I went with Cloudflare.

Netlify has a credit-based system that charges for builds, bandwidth, form submissions, and serverless function invocations. Each resource consumes credits from your monthly allowance. It’s flexible, but hard to predict what you’ll actually pay.

Vercel is more straightforward. The main limit is bandwidth (100GB/month on free). That’s probably fine for most blogs, but it’s still a limit you have to think about.

Cloudflare Pages has unlimited bandwidth on the free tier. I like unlimited and free. Great combination of words. The only limits are 500 builds per month and 100 custom domains, neither of which I’ll hit.

Setting Up Cloudflare Pages

- Go to Cloudflare Pages

- Click “Create a project” → “Connect to Git”

- Select your GitHub repo

- Cloudflare auto-detects Astro. Build settings should be:

- Build command:

npm run build - Build output directory:

dist

- Build command:

- Click “Save and Deploy”

Your site is now live at your-project.pages.dev. Every push to main triggers a new deployment automatically.

To add your custom domain:

- In Cloudflare Pages, go to your project → Custom domains

- Add your domain

- Update your DNS to point to Cloudflare (they’ll walk you through it)

That’s it. Every git push triggers a build that deploys globally in about 20 seconds.

The Speed Difference

Here are my PageSpeed Insights scores:

WordPress (before):

- Performance: 67

- First Contentful Paint: 1.7s

- Largest Contentful Paint: 7.2s

- Total Blocking Time: 290ms

- Speed Index: 4.6s

Astro on Cloudflare (after):

- Performance: 100

- First Contentful Paint: 0.2s

- Largest Contentful Paint: 0.5s

- Total Blocking Time: 0ms

- Speed Index: 0.5s

A perfect 100 performance score! And LCP went from 7.2 seconds to half a second. That’s a 14x improvement.

The site just… loads. Instantly. On mobile. On slow connections. Everywhere.

And I’m not even trying that hard. I haven’t done any advanced optimization. This is just what happens when you ship static HTML instead of a PHP application with twelve plugins.

My New Content Workflow

This is the part I’m most excited about.

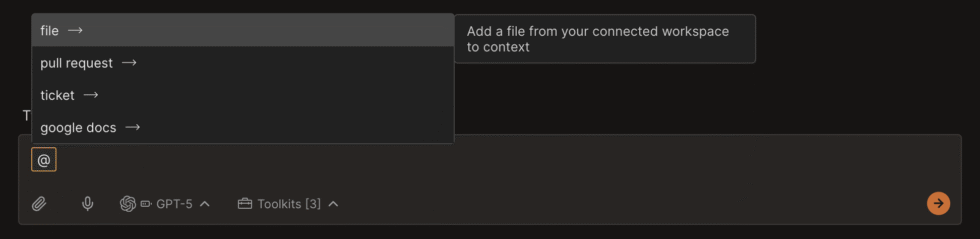

Now that my blog is just code, Claude Code now becomes my content creation partner.

Writing With Claude Code

I open my blog project in the terminal, start Claude Code, and say “let’s work on a new blog post about X.” Claude Code has access to every post I’ve ever written. It understands my writing style, my formatting patterns, which topics I’ve covered, how I structure tutorials versus opinion pieces.

I can ask it to suggest topic ideas based on what’s resonating in the AI space, or I can come in with a specific idea and flesh it out together. The conversation might go:

Me: "I want to write about building AI agents from scratch.

What angle would complement my existing content?"

Claude: [reviews my posts] "You have the Claude Code guide and the

context engineering piece, but nothing on the fundamentals.

A 'build a baby coding agent in Python' tutorial would fill

that gap and give readers a foundation before your advanced stuff."

Me: "Perfect. Let's outline it."

We go back and forth. I provide direction, Claude Code drafts sections, I course-correct, it refines. When we’re happy with the draft, it creates the MDX file in src/content/blog/ with proper frontmatter.

Editing and Refining

The output is a markdown file. I can open it in VS Code, Obsidian, or any text editor and make changes directly. Claude Code’s draft is a starting point, not the final product. I’ll tighten the prose, add personal anecdotes, cut sections that feel fluffy.

Read more about how I create content with AI while avoiding slop here: My AI Writing Process

When I’m done editing, I save the file and tell Claude Code to push:

claude> Commit and push the new blog post

Done. Live on my site in 20 seconds.

The Speed Difference in Practice

From idea to published post:

Old workflow (WordPress): 5-6 hours minimum. Lots of context switching between tools, waiting for editors to load, copying embed codes, previewing.

New workflow (Claude Code + Astro): 2-3 hours for a substantial tutorial like this one. One tool, one conversation, one push. And most of that time is me editing.

Should You Do this?

This whole process took me an afternoon. And at the end of it, I realized that I’m not rolling my own CMS. I don’t need any of the standard CMS features.

This approach works if:

- You’re a solo blogger or small team

- You’re comfortable with code (or have an AI coding agent)

- Your content has one primary destination (your website)

- You don’t need approval workflows, role-based permissions, or audit trails

This approach may not work if:

- You have non-technical team members who need to edit content (although maybe you can train them on this workflow)

- You need content to flow to multiple destinations like apps and emails (although Claude Code can handle this)

- You need structured data with relationships and queries

- You have compliance requirements that need proper audit trails

- You’re publishing at high velocity with multiple contributors

Sanity’s right that large teams need a CMS. But for everyone else, the markdown + git + coding agent workflow is so much better.

My blog is now:

- Faster – Perfect 100 PageSpeed score, sub-second loads

- Cheaper – $0/month vs $20/month

- Simpler – No plugins, no database, no security updates

- AI-native – Claude Code can create, edit, and publish content directly

In fact, I’m also in the process of launching my new AI consultancy, Hiyaku Labs, and one of our partners, who is an expert designer, has been struggling with Framer. After showing her what I did with my personal blog, we decided to do the same for Hiyaku Labs, and built the full site in 2 hours.

Check it out at hiyakulabs.com

So, if your CMS-hosted site feels sluggish, or you’re struggling to get the design right, or all the extra steps and complexity are frustrating you, it might be worth a shot.

Your content is just code now.

I’ll update this post once the full migration is complete with any lessons learned along the way.